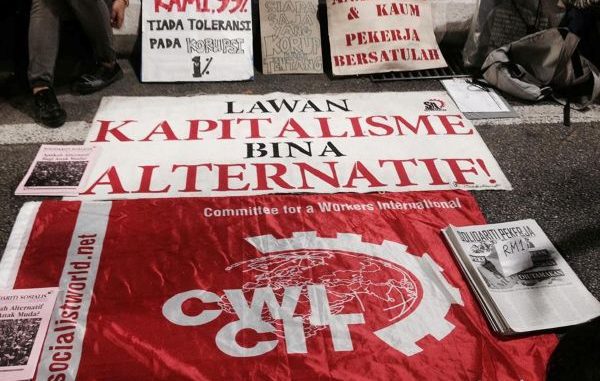

A national meeting of Sosialis Alternatif (SA) Malaysia, the CWI in Malaysia, was held from 16–18 January on Pangkor Island, off the coast of Perak in the Straits of Malacca. The discussions included several newly recruited youth members attending their first political event with SA. The meeting opened with international perspectives led by Yuva, analysing the unprecedented global developments arising from the protracted crisis of capitalism. These perspectives provided the anchor for subsequent discussions on Southeast Asian regional dynamics, led by Kelvin, and Malaysian national perspectives, led by Johan.

Since World War II, the expansion of global capitalism has produced highly integrated supply chains and interdependent markets, binding regions such as Southeast Asia tightly to fluctuations in the world economy. Within this system, Southeast Asian economies were incorporated as sites of low-cost manufacturing and resource extraction, oriented toward export markets dominated by foreign capital. Today, as capitalism enters a prolonged crisis characterised by stagnation, mounting debt, and sharpening geopolitical rivalry and realignment, these same production networks have become sources of acute vulnerability rather than stability, exposing regional economies to external shocks, investment volatility, and intensified exploitation.

South East Asia

As major powers such as the United States and China intensify their confrontation over technology, maritime routes, and access to strategic resources, peripheral economies are increasingly drawn into this rivalry rather than insulated from it. China’s growing pressure on Philippine outposts in the Spratly Islands and its challenges to Filipino access within the country’s exclusive economic zone for example have heightened regional insecurity, compelling governments across Southeast Asia to reassess economic and political priorities from defence spending and military alignment to trade relations and foreign partnerships under conditions not of sovereign choice, but of mounting great-power coercion.

In the Philippines, repeated confrontations in the South China Sea have elevated maritime security and expanded military cooperation with the United States to central state priorities, diverting public resources toward defence while social needs remain unmet. These geopolitical pressures have intersected with domestic political crises, particularly public anger over corruption and the misuse of state funds exposed during major flood disasters last year. The result has been growing social discontent expressed through protests, grassroots mobilisations, and actions involving trade unions and socialist organisations.

In Indonesia, rising living costs, corruption scandals, and slowing economic growth have similarly triggered repeated protests and anti-government demonstrations. These mass upsurges, however, have increasingly been met with repression, including the deployment of troops and the expansion of the military’s role in civilian affairs. Under the administration of Prabowo Subianto, the state has relied more openly on the armed forces to contain dissent, reflecting how deepening social tensions under capitalist crisis are being managed not through reform, but through coercion and authoritarian consolidation.

Meanwhile, in neighbouring Myanmar, the protracted civil war that followed the 2021 military coup has deepened into a widespread conflict involving ethnic armed groups and mass displacement, underscoring how capitalist competition both internal and external, interacts with long-standing social fractures. In Thailand and the Philippines, the interplay between external strategic pressures and internal democracy deficits reveals similar patterns. Thailand’s political crisis rooted in the blocking of reform mandates by entrenched elites reflects how capitalist states resort to authoritarian measures when faced with social discontent and economic stagnation.

Malaysia

In Malaysia, the long-heralded promise of post-pandemic growth has been undermined by the deeper contradictions of world capitalism in crisis. Official estimates suggest the economy continued to expand moderately in 2025 with GDP growth at around 4–5 %, supported by services and domestic demand. Yet this nominal growth masks pressures on wages, stagnant productivity, and rising living costs that fail to keep pace with everyday needs. These conditions have fed public frustration with Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s government, which came to power on reformist promises but has implemented austerity-leaning measures such as sales and services taxes and subsidy cuts that have increased burdens on ordinary people. In July 2025, thousands of Malaysians rallied in Kuala Lumpur under the slogan “Turun Anwar” (Step Down Anwar) in response to rising costs of living and unfulfilled reform expectations, marking one of the most significant protests in years.

At the same time, growing labour mobilisation has begun to resurface. Such as the union busting and gig workers protests in front of the parliament demanding better and secure pay for workers. Also worth mentioning NUBE (National Union of Bank Employees) where picket actions and May Day gatherings has gained more tractions among workers in the union. While these movements have not yet coalesced into a sustained, unified working-class uprising, they reflect a growing impatience among youth, and workers who see the current political leadership as incapable of addressing inequality, corruption, and economic insecurity.

Anwar Ibrahim has increasingly relied on elite compromise to maintain a fragile parliamentary majority, most visibly in the soft-pedalling of accountability for figures long associated with grand corruption and authoritarian avoidance of justice. The selective and cautious handling of cases linked to 1MDB Najib Razak and the political rehabilitation of deputy Prime Minister Zahid Hamidi have fuelled public cynicism, reinforcing the perception that the legal system remains subordinated to political expediency rather than genuinely independent rule of law. This erosion of credibility at the centre has fed into electoral responses on the periphery, most clearly seen in Sabah, where recent state-level voting patterns reflected a rejection of federal coalitions in favour of local nationalist and regionalist parties, signalling disillusionment not only with UMNO’s legacy but also with Pakatan Harapan’s failure to decisively break from old power structures.

Organisation and youth

The national meeting also reviewed the organisation’s overall development, including growth in membership, publications, workers’ campaigns, and financial capacity, in a discussion led by Qira. This was followed by a session led by Zufar focusing on political consolidation and organisational tasks for the coming period. Notably, the past year saw significant growth among university students, prompting a dedicated discussion on youth and Gen-Z work. This session emphasised the importance of clearly distinguishing radicalism from mere rebellion, as part of building a disciplined, cadre-centred organisation. The discussion also examined how SA’s youth work can play a strategic role in deepening working-class struggle and linking student activism to broader movements of labour and social resistance.

Held amid deepening global crisis and regional instability, this national meeting marked a decisive step forward for Sosialis Alternatif as part of the Committee for a Workers’ International. The discussions reaffirmed that the crises unfolding across Malaysia and Southeast Asia as the task ahead is not reformist adjustment, but organised working class struggle towards a democratic socialists conclusion. It is more important than ever to consolidate and politically educate a growing layer of youth and student members into revolutionary class struggles and to strengthen regional collaboration across Southeast Asia in response to shared class conditions shaped by global capitalism.