South Africa is going through its most serious economic crisis of the democratic era. What this crisis shows, probably more than any other before it, is that there is no solution on a capitalist basis. The crisis has been produced by the very policies the capitalist class has enforced on their executive committees – capitalist governments worldwide, including the African National Congress in SA. The scientist and socialist, Albert Einstein, defined insanity as doing the same thing over and over again but expecting a different result. Yet this is precisely what capitalist governments are doing worldwide. SA is no exception.

Annual growth in GDP (gross domestic product – the total value of goods and service produced) is the worst since measurements began in 1946. With every sector of the economy affected, analysts are in a competition to find the right words to describe the extent of the crisis. One analyst predicts that a “financial tsunami” is about to hit:

Record unemployment, stagnant economic growth, government debt levels rocketing from 25% of GDP in 2009 to an expected 60% by the end of this year. There are today more people on social grants (17,3m) than those who earn a living. The residential property market has now moved sideways for 11 years and in real terms is down 23% when inflation is factored in. The JSE has just had its worst 5-[year] period on record and the rand has collapsed from R6, 80 [to the dollar] in 2012 to around R15 today. South Africans are infinitely worse off today than 5 and ten years ago.[1]

The retail sector share price collapse is described as “an apocalypse[2] and the mining industry are feared to be entering its “last chapter”[3]. Construction heavyweights Group Five and Aveng have applied for business rescue and one of the oldest, Murray & Roberts, is exiting the sector altogether. By September, nine out of ten manufacturing sectors had shrunk. Mall building is said to be “a bubble waiting to pop”.[4] The worst drought in a thousand years is affecting agriculture in three provinces. The 127-year old Tongaat Hullett is pulling out of sugar production. Another analyst:

Gross fixed capital formation — a gauge of new investment into the economy — fell 4.5% in the first quarter of 2019 from the prior three months … as SA’s economy extended its weakening cycle to the 67th month in a row.[5]

The downward trend in SA’s business cycle has continued since the end of 2013, the longest downturn since 1945.[6] Worse still, economic growth prospects have been revised downwards for the ninth year in a row. There is no prospect of economic growth in 2019 – predicted at between 0.5% and 1% and expected to persist at these levels, unable to recover to anywhere near the modest target set by the National Development Plan in 2012. The National Planning Committee that SA President Ramaphosa chaired calculated that growth of 5.4% a year for ten years consecutively would be required to eliminate extreme poverty and achieve full employment by 2030.

By September this year, a shocking number of South Africans were living below the food poverty line. To feed a family of four a nutritionally complete basket of food, costs R2,327 per month. But more than half the population live on less than R1,230; a quarter on less than half that at R19 per day. The child support grant of R420 per month cannot adequately feed its 12.3 million recipients.[7]

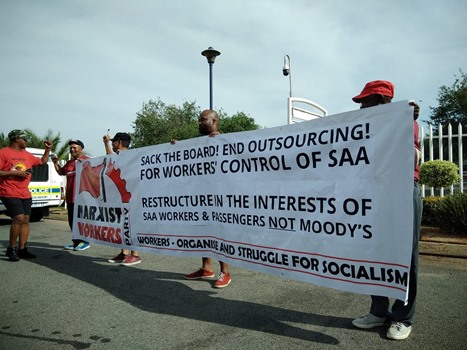

Despite unemployment having reached a record 10.2 million, the jobs bloodbath continues. The airline, SAA, wants to retrench 944; PRASA’s job losses will reach 10,000 by the end of this year; Saldanha Bay’s closure will destroy 2,000 jobs; 10,000 in banking; the mining industry is threatening 100,000 job losses if the carbon tax is introduced next year. It is abundantly clear that the capitalist class and its executive committee, the ANC government, have only one “solution”: to place the burden of the crisis on the shoulders of the working class.

What lies at the root of the crisis?

Despite hypocritical posturing as champions of the nation’s interests, capitalists do not invest for the good of the economy or the people. They invest to make a profit. But depressing wages and retrenchments means consumers do not have enough money to buy the goods they themselves produce – this is what is meant by “demand” – consumer purchasing power.

How did the ANC government and their capitalist masters attempt to solve this problem? By making it easier for consumers to put money in their pockets – inflating demand – by deregulating the financial markets, and encouraging unsecured lending from 2007, onwards. Not only did this policy fail, it created a new problem – indebtedness. Today consumer debt sits at R19.2 trillion, higher than Angola’s GDP. Annually, 72% of household income is spent on debt servicing but still 10.2 million are in arrears.

Manufacturing’s decline means SA’s income from exports is lower than the cost of imports creating a deficit in the current account, and undermining the Rand. To “solve” this problem the SA Reserve Bank introduced “inflation targeting”. Its real aim was to prop up the Rand by attracting foreign direct investment through maintaining interest rates at a higher level than SA’s major trading partners. The SARB has stuck stubbornly to this policy despite interest rates having fallen to historic lows worldwide. Addicted to this “carry trade” it cannot afford to abandon it without these parasitic inflows drying up, exposing the deficit in the overall balance of payments and threatening the Rand.

But this, in turn, created another problem. These ‘investors’ do not have the slightest interest in creating jobs. They want to make a fast buck by borrowing at low rates in the advanced capitalist countries and investing in SA’s higher interest rates to make an overnight profit. This is why these portfolio flows are referred to as “hot money” – it leaves the country as quickly as it enters. At the same time manufacturing has continued to decline. The level of investment has fallen to below replacement costs of worn out machinery, equipment and plant, as Treasury warned in 2016. The combination of the resultant falling productivity and an overpriced Rand has left the local capitalists unable to compete on a world market in which trade has fallen in any case for lack of demand.

This has further severely constricted demand which makes up 60% of GDP. Without demand for their goods, the capitalists therefore cut back on investment, hoarding their money or taking it out of the country by legal and illegal means. State expenditure accounts for nearly a third of GDP. Cutting back state spending, freezing or cutting wages, retrenchments, all cut demand. The capitalists and their government resemble a starving animal feeding itself on its own entrails.

Estimates of corporate hoarding vary from R1.5 trillion to R3 trillion. Illicit capital flows are estimated to have reached R147 billon between 2003 and 2012.[8] A study that Treasury itself participated in found that the top 10% of the 2,000 foreign multinationals operating in SA account for 80% of the R7 billion a year SARS loses in tax. The overall effect of these polices has been continued deindustrialisation. Manufacturing’s contribution to GDP, the bedrock of any modern economy, has declined whilst finance’s has risen.

The combination of cuts in government spending and low wages lies at the root of the capitalists disinterest in investing in SA. A total of R70 billions of cuts to public sector spending have been implemented since 2014. Wages have declined from 54% of national income in 1994 to 46% today. The capitalists want to have their cake and eat it. They demand spending cuts but complain about the decline in government tenders for infrastructure projects. They demand cuts in public sector wages and social spending but the retail bosses complain that the slow-down in social grant increases has led to lower demand for their goods.

Analysts say that the lack of investment is due to a fall in business confidence reported by the South African Chambers of Industry to be at the lowest levels since 1985. But the problem is not the psychology of the capitalists. It lies in the laws of the capitalist system itself. Capitalism is based on profit which is made through the unpaid labour of the working class. To make a profit, the capitalist must pay the worker as little as possible. When capitalists sell their commodities they price them on the basis of at least the total amount of labour time the worker has expended producing them. But the worker is also a consumer. To enable the worker to buy commodities the capitalists should pay as much as possible. But to make a profit they must pay as little as possible. The capitalists cannot do both. Under capitalism, this contradiction is irreconcilable.

What would a rating agency downgrade mean?

Hardly a day passes without the capitalists screaming that ratings agency Moody’s, the only one of the three that has not downgraded SA to junk yet, is poised finally to do so. Moody’s November decision to reduce SA’s outlook to negative is said to be a final written warning. Ramaphosa has three months to implement reforms they warn. If there are no credible plans by the February 2020 budget, a downgrade to junk is said to be a certainty.

Although there is undoubtedly an element of propaganda in the capitalists downgrade doomsday prophesies, the working class must be prepared for the possibility. A downgrade could trigger a flight of capital of possibly as much as R300 billion, a collapse of the Rand, and then a massive hike in interest rates to prop it up. This would plunge the economy into a deep recession.

The capitalist can, and will of course, take their money and run, as many of them are openly boasting. For the working class a disaster would turn into a catastrophe, dragging the middle class down into their ranks. The rate of liquidations and bankruptcies and mass unemployment will accelerate. The higher interest rates would ripple throughout the economy resulting in higher prices for basic commodities, house repossession – already standing at 10,000 a year – as well as furniture and cars, and defaults in loan repayments. Inflation will target the working class even more viciously than it has throughout the lifetime of this policy for which, SARB governor, Lesetja Kganyago has won the prize of Central Banker of the Year from his international counterparts.

It would, in other words, solve absolutely nothing economically. At present the government borrows R850 million every working day to finance the R57.5 billion budget deficit and continue paying salaries and maintaining social services. A downgrade would result in SA being kicked out of the FTSE World Bond Index compelling the government to offer even higher rates to borrow the money to finance the deficit. With interest on debt already the biggest item in the budget, borrowing could climb to R1 billion a day or more.

The “reforms” the capitalists are demanding show that they are fully committed occupants of Einstein’s lunatic asylum. They want a repeat, only more aggressively, of the very same polices that have wreaked havoc with the economy and working class living standards. To pull SA back from the edge of the ‘fiscal cliff’ and prevent a default on its debt, Ramaphosa is being urged to tighten the noose of ‘fiscal consolidation’ around the necks of the masses. This means cuts in government spending of R150 billion over the next three years, and ‘structural reforms’, such as full or partial privatisation of SOEs starting with Eskom and SAA.

The most deafening hysteria is on the public sector wage bill which has risen to 46% of budget spending. ‘Savings’ will be achieved by cutting at least 30,000 government and 16,000 Eskom jobs; a freeze or cut in wages and benefits. In addition the bosses are demanding an end to non-payment for electricity to recover, for example, the R17 billion owed by Soweto residents. Mboweni insists that e-tolls should be paid.

Can economic recovery be stimulated?

There is growing criticism of government policies from those who believe the capitalist system can be managed more rationally. Amongst the most vocal critics of SA’s neo-liberal economic policies is Duma Gqubule:

For years, the Treasury has been buying time, telling us things will get better if we take its medicine of austerity and structural reforms. When the medicine does not work, it doubles the dose — as with the “new” strategy and austerity measures — or repackages the ingredients.

Correctly arguing that SA has an aggregate demand problem, he denounces the idea of simultaneously introducing a stimulus and continued austerity as an “oxymoron” (i.e. mutually contradictory). Echoing calls for an end to inflation targeting, he makes various proposals including funding the SOE deficits from the surpluses in the Government Employees Pension Fund, UIF and SA Reserve Bank freeing the government to increase spending on e.g. infrastructure, thus encouraging firms to invest, stimulate consumption spending, investment and jobs.

These are not new or particularly original ideas. Far from lower interest rates and quantitative easing (printing money) encouraging capitalists to invest, create jobs and thus stimulate economic growth, in the major economies, this ‘easy money’ was used to buy back shares in their own companies, boosting share prices and outlandish bonuses for these “achievements” without jobs, and buying rival companies.

A global depression was averted, but not the underlying contradictions of capitalism. Economic growth has been weak, failing to return to pre-2008 levels. Most new jobs are precarious and low paid. Inequalities have widened to historic levels. Demand has remained flat as has investment.

The new IMF head, Kristalina Georgieva, warned that the world is in a “synchronised slowdown”, with slower growth expected across nearly 90% of the global economy. She said central banks use of low interest rates to boost activity had led to a build-up of corporate debt. There is a risk of a $19 trillion default in the event of a major economic downturn and half of the world’s top ten banks would collapse.[9]

Way out

SA’s neo-Keynesians (followers of Modern Economic Theory) are therefore calling for SA to imitate polices that have failed in much more powerful economies. They ignore the historical conditions that created the post-World War II economic boom and the high levels of government intervention, social spending and wage rises that accompanied it (coinciding in South Africa with the period of ‘High’ Apartheid). Ultimately, the boom undermined itself as the iron laws of capitalist economics reasserted itself with a vengeance.

Today the wealth exists to end mass unemployment and poverty. The problem is that the commanding heights of the economies of the world are privately owned and production takes place for private profit. This barrier can only be overcome by the overthrow of capitalism and the socialist transformation of society – replacing private ownership by social ownership and organising production for social need.

The world economic crisis has undoubtedly produced differences of opinion as the attack on the ECB’s negative interest rates by the German Bundesbank CEO shows. They are in a panic. Johann Rupert says the possibility of an uprising by the masses keeps him awake at night. But they differ not over the need for capitalism but how best to manage it. The only force with an interest in, and the capacity for, the socialist reconstruction of society is the working class. But the working class must be organised for mass struggle and armed with a socialist programme.

[1] “Hit by a Financial Tsunami”, Magnus Heysteck, Biznews (16 October 2019)

[2] “SA’s Retail Apocalypse: How Retailers Lost Their Game”, Adele Shevel and Marc Hasenfuss, Business Day (5 September 2019)

[3] “Gold Street is where SA’s Mining History Goes to Die”, Ana Monteiro and Felix Njini, Fin24 (20 June 2018)

[4] “Mall Mania: A Bubble Waiting to Pop”, Joan Muller, Business Day (30 May 2019)

[5] “Businesses Balk at Spending on Fixed Assets”, Karl Gernetzky, Business Day (27 June 2019)

[6] “South Africa Stuck in Longest Business-Cycle Slump Since 1945”, Prinesha Naidoo, Bloomberg (27 June 2019)

[7] “More than Half of South Africans Living on Less than R41 a Day”, BusinessTech (8 October 2019)

[8] “R147 Billion Lost Through Money Illegally Leaving SA”, Sarah Evans, Mail & Guardian (16 December 2014)

[9]“New IMF chief calls for united effort against global slowdown”, Sarah McGregor, Business Day (8 October 2019)