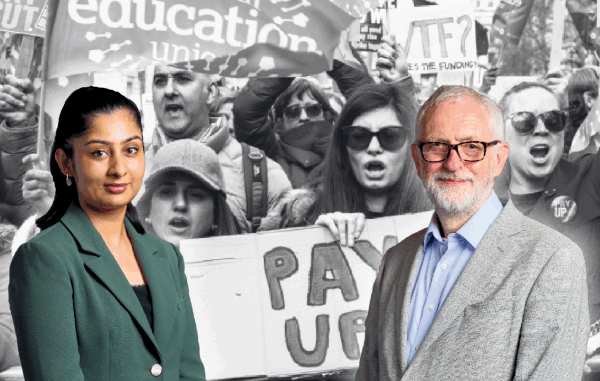

In one week, more than 700,000 people have signed up to the yourparty.uk website to support Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana’s initiative to build a new left party. The party doesn’t yet exist, and so there is not yet a membership fee. Nonetheless, this figure shows huge enthusiasm for the party. It tops the highest membership in Labour’s history: achieved when Jeremy Corbyn led it. It has reached as many as the current membership of Labour, Tories, Liberals and Reform combined.

A year ago, in the immediate aftermath of the 2024 general election, the Socialist Party pointed out the extremely shallow base of support for Starmer’s Labour, elected by just 9.7 million voters, 20.1% of the electorate, the lowest share for any incoming government since the first ever election fought under universal (male) suffrage in 1918. We drew a contrast with the votes Labour received when Corbyn was leader, pointing particularly to the 12.9 million his anti-austerity manifesto received in 2017.

Unsurprisingly, these basic facts were not being reported in the establishment media at the time because, as we explained, “the capitalist class wants to boost the authority of the incoming Labour government hoping that, despite its very shallow social base, it will still be able to implement a programme in the interests of the elites. They are also desperate to cement the lie that Corbyn’s policies were unpopular. Despite their best efforts, however, this government will be rocked by mass working-class struggles against it, which will also inexorably find a political expression.” (Socialism Today July 2024)

Just 12 months later and the potential power of that political expression has become palpable. Even just the promise of a new party has lifted the confidence of all those suffering pay restraint, cuts to public services and benefits, and watching with horror the unimaginable misery being suffered by Palestinians in Gaza at the hands of the Israeli state. While our chins have been lifted, those of the capitalist class and their political representatives have dipped. Polls even before a party was announced showed that 18% of people would consider voting for a party led by Corbyn, and that it would come first among young people.

Labour loyalists are desperately beating the drum of ‘vote for us or get Reform’, but it is not working. Too many people can see that, if the workers’ movement supports this Labour government for the rich it will be a gift to Reform, who will be able to falsely pose as the representatives of the ‘little people’. If, on the other hand, a mass workers’ party is built with a fighting, anti-austerity programme, it would cut across Reform. One recent Merlin Strategy poll gave an indication of how – despite all of the slanders of the capitalist press – Reform voters still perceive Corbyn as representing something different to the establishment politicians. It found 67% of them think he is for working people, 64% believe he is honest and principled.

Debates on the way forward

Inevitably, the mainstream media has attempted to poke fun at the allegedly chaotic announcement of the initiative, and the fact that there are different views at the top on the character and structure of a new party. Correctly, Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana have both shrugged off these smears, explaining that a democratic debate involving all those who have signed up can only be positive.

This is absolutely correct. The potential for a new party could not be clearer, but of course that does not mean success is guaranteed. Previous opportunities have not come to fruition. Most recently, during the strike wave three years ago, half a million people signed up to Enough is Enough hoping it would be a new party. Enough is Enough was launched by RMT general secretary Mick Lynch and CWU general secretary Dave Ward, both unions at the forefront of the strikes. The strike wave had, as Mick Lynch correctly said at his union’s 2023 annual conference, “revived the trade union movement, putting our values and our policies back into the mainstream in this country”. The working class and its unions were back as a leading force in society, able to shape events. But no party was launched to give that an electoral expression and Enough is Enough dissipated. This time a major step forward has been taken – a new party is going to be launched – but the way that is done could be decisive to its longer-term success or failure.

First and foremost, we need a party based on the working class. Capitalism is a system based on the exploitation of the majority for the profits of the few. Our class is potentially the most powerful force in society. As the pandemic laid bare, the working class keeps society running, and it can also bring it to a halt. In this era, the working class is probably a bigger majority in society than ever before. The living standards of many who had previously considered themselves middle class have been badly eroded, and, like the doctors, they are increasingly adopting working-class methods of struggle.

Our class has the power to transform society. At this stage, however, the working-class majority has no mass party of our own, while the capitalists have plenty. Establishing a mass workers’ party would be a vital step forward in realising our class’s potential strength. With a fighting socialist programme, it would also be able to win the support of many of the middle layers of society, including small businesspeople and farmers.

It is therefore very positive that Zarah Sultana argued at the ‘trade unionists for a new party’ meeting hosted by Dave Nellist on 21 July 2025 “for a party that stands with workers not the wealthy, a genuine democratic socialist alternative that is rooted in the trade union movement and built by and for our class, the working class.” However, in her subsequent 28 July 2025 interview with Novara Media on a new party, she said that One Member One Vote (OMOV) would be the best way to build the kind of party we need. In our view that is mistaken. Jeremy Corbyn outlined a better proposal when he said, in his interview with Owen Jones (30 July 2025), he thought the party “would end up with some kind of federal nature and trade union involvement will be an important part of it”.

Record of OMOV in the workers’ movement

Undoubtedly for many of the hundreds of thousands who want to be part of a new party, OMOV would initially appear a very democratic way of taking decisions. However, there was a reason that former deputy prime minister John Prescott credited OMOV with being central in the 1990s to the transformation of Labour into the ‘New Labour’ party that the capitalist establishment could wholly rely on. In fact, he considered it more central than the abolition of Labour’s socialist clause in its constitution, ‘Clause IV’. OMOV was a means of using the more passive members – those sitting at home and seeing debates within the party via the capitalist media – against the more active layers who participated in those debates via the democratic structures of the party.

Crucially, it was also central to undermining the strength of the collective role of the trade unions within the party in deciding policy, selecting candidates and its general governance. Labour was founded as the voice of the trade union movement. Prior to Tony Blair’s establishment of ‘New Labour’, Labour had been a ‘capitalist workers’ party’ – so its leadership did defend the capitalist system, but it had a mass working-class base which was able to pressurise the leadership via the party’s structures. That meant, for example, that when the Labour government threatened to introduce the ‘In Place of Strife’ anti-union laws in 1969, the opposition of the trade unions split the Cabinet and quickly led to the legislation being dropped.

Of course, the old trade union ‘block vote’ in the pre-Blair Labour Party is not a model for a new party. It was often wielded by right-wing trade union general secretaries without any democratic checks via union structures. Trade union representation in the new party should be under the democratic control of trade union members.

Today there are more than six million workers in trade unions. In those which are still affiliated to the Labour Party, including the biggest three – Unite, GMB and Unison, there is huge anger about paying members’ money to a party that is attacking workers. That was epitomised by the emergency motion at Unite conference, which agreed to reassess the union’s relationship with Labour. Across the whole trade union movement – affiliated and unaffiliated – there is growing enthusiasm for a new party that stands in workers’ interests. A battle is going to rage in the unions between those who want to cling to Labour, and those who want to support a new party, and the stakes are high. If even a quarter of the trade union movement, inevitably sometimes on a local rather than national basis in the first instance, joined with a new party, the absolute numbers, and more importantly the social weight because of their collective power, would far outweigh the very impressive 700,000 who have signed up as individuals.

However, OMOV would not allow the collective voice of the trade union movement to have any weight within a new party. Active trade unionists understand the concept of representative workers’ democracy. Union branches elect delegates to trade union conferences to represent their interests, and would require the same right approach of a new party.

Of course, Zarah Sultana will certainly not have been thinking of John Prescott and Tony Blair when she enthused about OMOV. Probably her concept is closer to that of Podemos, the anti-austerity party that was founded in Spain in 2014. Branches, or ‘circles’ exist in Podemos, but without decision making powers. It was conceived as a ‘horizontalist’ party with votes taken by all members online. While this sounds democratic, it actually leaves decision making in the hands of the small group that are setting the questions.

To give a concrete example, one of the issues that has already come up for debate is whether and how to cooperate with the Greens. James Schneider, co-founder of Momentum, argued for ‘joint open primaries’ with the Greens, and Zarah Sultana seemed to suggest electoral agreements with them in order to block Reform. Jeremy Corbyn had, in our view, a better approach when he said that, while the party should work with the Greens on individual issues, he did not favour an alliance with them because they are not a socialist organisation. We would add they are not a party based on the working class.

It is absolutely correct for these issues to be thoroughly debated in a new party. But if that is done just via online questions it will not be a genuine debate. If members were asked ‘is cooperating with the Greens in order to maximise the left vote a good idea?’ a positive answer would be overwhelmingly likely. If on the other hand, they were asked ‘would you favour the party standing down in the local elections for Green councillors with a record of voting for austerity in the council chamber?’ a negative response would be most likely. Leaders from the top determining how ‘discussions’ are framed is not democracy from below.

So how could a federal structure work?

Jeremy Corbyn’s suggestion of a federal structure is not a new one. We have long pointed to the history of the Labour Party – which began as a highly federal organisation with representation from different trade unions and socialist organisations – as the best basis for a new mass workers’ party, especially in its early stages. On a much smaller scale the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC), an electoral coalition which the Socialist Party takes part in, over fifteen years has successfully used a federal ‘umbrella’ structure to bring together disparate forces to contest elections on an anti-austerity basis including, for ten years, a national trade union, the RMT, with 80,000 members.

Of course, something more developed than TUSC’s very simple structure will be needed for a party on the scale that is now possible. A founding conference with delegates from affiliated trade unions, affiliated political and working-class community organisations, plus groups of independent councillors would be a good first step. It is positive that Jeremy Corbyn has indicated he supports autonomy for the party structures in Scotland. The same should also apply in Wales.

Local members’ organisations – branches or districts covering a local council area – could also have representation at national conferences as the party develops. They could also operate on a federal basis, again taking the best traditions of the Labour Party. Local district committees could again have delegates from more localised units made up of individual members, probably based on wards, plus affiliates, a youth wing and so on.

Some may argue that such a federal approach would be an obstacle to building a fighting party that is involved in struggle, but the opposite is true. For example, in the 1980s the Socialist Party – then Militant – played a leading role in the mass struggle of Liverpool City Council against the Thatcher government. The District Labour Party (DLP) was the key body via which the course of the struggle was decided at each stage. It had more than 600 delegates from unions, ward Labour parties and so on – there as representative delegates, not accidental individuals – and was a kind of parliament of the workers’ movement, setting policy for councillors to implement, and organising action ‘on the street’ like rallies and demos to support their stand. The creation of a party able to play that role in the many struggles ahead would be a tremendous step forward.

The political role of a democratic structure

A democratic structure is not secondary; it will be crucial to this party developing the kind of political programme and fighting determination that the working class desperately needs. It is already clear that this new party will inevitably face an avalanche of slander from the capitalist media and establishment, as they try to pressurise its leadership to become more ‘moderate’ and ‘respectable’. Bowing to that pressure would ultimately mean becoming just one more capitalist party. A structure through which the working class can apply strong counter pressure, holding the leadership accountable, will be essential.

It would also be important for scrutinising forces that join the party – particularly those that are already councillors or MPs for Labour or the Greens. Of course, it is welcome if councillors and MPs break with their existing parties to join a party with a clear anti-austerity programme, but that will not be the only motivation for switching parties.

Ten years ago, in Greece, Syriza – the Coalition of the Radical Left – came to power on an anti-austerity programme. In the course of a few months, the Syriza government capitulated to the demands of the institutions of capitalism and implemented austerity. One factor was that, seeing the party heading towards power, MPs from PASOK – the equivalent of Labour – jumped ship and joined Syriza. They did that partly to try and save their own careers, but also as conscious agents of the capitalist class, working from the inside to make the party safe for the ruling elite. Councillors who continue their record of voting for cuts to local services and workers’ pay and conditions should not expect to be welcomed unchallenged into the new party.

The role of the Socialist Party

Of course, no matter how well the new party is organised, it will not be possible to prevent attempts at sabotage by agents of the capitalist class both inside and outside the party to try and prevent its programme being implemented.

It is not yet known what that programme will be, but something like Jeremy Corbyn’s 2017 manifesto is a possibility. Its headlines of nationalising the privatised utilities, mass council housebuilding, rent controls, abolition of tuition fees, a green new deal and removal of anti-trade union laws, were all enormously popular.

The Socialist Party campaigned enthusiastically for that manifesto as a step forward for the working class, as we would again for a similar one. However, we also warned that – given the inevitable attempts of the capitalist class to prevent its implementation – to really build a society ‘for the many not the few’ will require taking decisive measures to take the levers of power out of their hands, such as nationalising the major corporations and banks under democratic workers’ control, and mobilising the working class in support of such a programme. These vital issues will inevitably be debated in any party that is serious about fighting in the interests of the working class, and the Socialist Party will be to the fore in arguing for the clear socialist programme that is needed.

In the meantime, we are contributing to the debate on how the party should be founded, not least by our campaigns in the trade union movement for engagement with the new party, not just giving passive support, but demanding that they are at the heart of its foundation.

We are also holding Socialist Party public meetings across the country, open to all. If you want to see the new party develop as a mass party of the working class, with socialist policies – come to a meeting in your area and join us in the fight for the party that workers need.