We are pleased to publish this extraordinary article by Trotsky’s former secretary, Rae Spiegel, later known as Raya Dunayevskaya. With thanks to CWI comrade, Wayne Scott, this is the first time the article has been transcribed into English and published. Written while Rae Spiegel lived and worked with Trotsky and his family in Mexico, it offers a rare and vivid portrayal of Trotsky in the final years of his life. Rather than presenting him only as a revolutionary leader and Marxist theoretician, the piece shows him as he appeared to those who shared his daily routine: a comrade, husband, and father living and working under conditions of immense political repression.

This was a period dominated by the Stalinist witch-hunt, which reached unprecedented heights with the Moscow Trials of 1936 to 1938. The Stalinist bureaucracy sought to eliminate the entire generation that had led the October Revolution. Trotsky’s supporters across Europe were being assassinated, new frame-ups were manufactured on a mass scale, and Trotsky himself was vilified as the supposed organiser of counter-revolutionary conspiracies that existed only in the imagination of the GPU. His family suffered terrible losses, and he lived under constant threat of assassination.

Raya’s account also captures the simple and disciplined conditions under which Trotsky lived in exile. Even basic comforts were regarded as unnecessary, and the household often had to manage with limited resources. As Raya notes, she and Trotsky’s wife, Natalia Sedova, would joke about the Stalinist claims that Trotsky received millions from Hitler at the very moment the household was rationing basic food.

Yet, as this article shows, Trotsky met these conditions not with bitterness or despair but with remarkable strength, discipline, and humanity. Raya’s account sharply contradicts the caricature promoted by bourgeois commentators who portray Trotsky as a cold or callous individual. Instead, we see a revolutionary fighter who combined political clarity with warmth, humour, and deep personal consideration for those around him.

Raya would later take a different political path. In the 1940s she joined C. L. R. James in developing the theory that the Soviet Union had become a form of state capitalism. In the 1950s she advanced what became known as Marxist Humanism. While Trotskyists disagree with many of these later conclusions, particularly where they blur the central role of the working class as the decisive force for socialist change. Her historical writings, especially on the struggle against racism in the United States, including her work on the Civil War, contain valuable insights.

But this article belongs to an earlier period, when, at twenty-two years old, she was a committed revolutionary of the Fourth International, assisting Trotsky during one of the most dramatic episodes in the history of our movement. After Trotsky’s assassination in 1940, she submitted the piece to Max Shachtman for publication in the press of the newly formed Workers Party, although it was never printed.

We are pleased to publish it now. In doing so, we aim both to counter the distortions and slanders directed against Trotsky for decades and to allow a new generation of workers and young people to encounter the real Trotsky, a revolutionary leader of the working class and, at the same time, a comrade of extraordinary humanity and integrity.socialistworld

Rounding out his second year on the North American continent, Leon Trotsky, at fifty-nine, is as optimistic and energetic as in 1902, when, as a twenty-two-year-old revolutionary, he made his first audacious escape from Siberia.

Work on two major biographies—one of Lenin and one of Stalin—dictation at the rate of 1,000 words per day, careful perusal of the world press, and checking and rechecking translations of his own works in five languages constitute only part of the daily routine of the ex-Soviet Commissar of Foreign Affairs.

Entrenched in the Blue House, which the Rivera’s have furnished for him in Coyoacán, Russia’s former Commissar of War is more heavily guarded now than in the days of his power.

The elaborate floodlights lend the residence the appearance of a Hollywood movie theatre during a world premiere. But the sentry box on the roof, the high walls, the barred windows and doors, and the intricate alarm system sharply alter that impression.

The structure now bears a resemblance to a virtually impregnable fortress. A sentry booth on either side of the alcázar houses police armed with bayoneted rifles, automatics, and shrill whistles. This is Mexico’s contribution to the protection of the noted exile.

A second line of defense is provided by inside guards—Trotsky’s devoted and unflinching revolutionary followers—who patrol the grounds. The well-armed secretariat staff assists them.

The muzzle of an automatic staring at us through a slight crack in the door was the response to our ringing. Apparently satisfied at the sight of Diego Rivera (who had driven me up from his home in San Ángel), the inside guard quickly opened the door and then quickly shut it.

I was introduced to Joe Hansen—a man of literary talent who had come from the Far West to serve as Trotsky’s English secretary. He in turn introduced me to Trotsky’s tall, reddish-blonde French secretary, Jean van Heijenoort, who led me into Trotsky’s study.

The spectacle of a household of armed men was not calculated to soothe the nerves of an American girl, and my uneasiness was heightened by the thought of the ordeal I would soon have to face. With little more than a year’s study of Russian, I dared present myself for the post of private secretary to an acknowledged master of the language. I was nervous: would my Russian stand up?

I half regretted that I had become so bored with my job in the States that I had left it for adventure in Mexico. Through my mind flashed descriptions of Trotsky as “dictatorial and exacting,” “a genius but a great egotist,” “arrogant.” I realized that I was actually afraid to meet the “Man of October”—so called because the day of his birth, October 25, coincided with the date of the successful Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.

With military stride Trotsky advanced toward me. He shook my hand firmly. I was instantly struck by his tremendous hand—the like of which I had never seen—the high forehead, the lion-like skull crowned with silver-gray hair flowing back as though touched by a breeze, the set jaw and chin upon which the gray moustache and goatee bristled. All of this was firmly set on enormous, sturdy shoulders.

A titan towered above me, and I felt the force of a great intellect. “Formidable,” I whispered in French to van Heijenoort.

To Trotsky I spoke in Russian. He smiled—the ingenuous smile of a pleased child—and said that my Russian had a perfect “Manhattan accent.” “But,” he continued in English, “you will do.” Then he added that perhaps I wished to “try him out,” referring to his newly acquired English.

Trotsky left the room for a moment and returned with a jacket for me. Mexican evenings are cool, but I was so exhilarated at meeting the famous exile that I had not noticed the chill. How had he noticed it? There was an unexpected simplicity about Russia’s former War Commissar that put me at ease, and I began to anticipate with pleasure the prospect of becoming his secretary.

But at dinner that evening my social poise suffered considerably when my mouth first encountered chile poblano. Even now I am not sure whether I swallowed the “flame projector,” as I later called the dish. Trotsky remarked that this was an international household and, glancing at my plate, added that no “national prejudices” were tolerated. The laughter at the table did not lighten my task, for my tongue was literally burning when I finished the chile poblano.

Despite the spirit of gaiety at the table, I still felt somewhat uncomfortable, for as a new member of the “family” I was under the surveillance of Trotsky’s keen eyes. Before we had finished dinner, I again felt his eyes measuring me; this time he disapproved of my extreme slenderness.

Solemnly, but with a twinkle in his eye, he summed up the situation: “Rae Spiegel—she does not exist. She is just a mathematical abstraction.”

Golden-haired Natalia Ivanovna (the wife of Leon Trotsky) took the remark so seriously that I was given double portions of chile poblano. Double portions had their effect, and when I left this genial family I was fifteen pounds the weightier…

The following day I was initiated into the daily routine. L.D.—as I soon learned to refer to Leon Davidovich—is up at 7:30. He waters the garden and takes a long walk in the patio. He is not to be disturbed, for it is then that he plans the day’s dictation, which begins at nine. Important articles, and of course his major literary works, are written in Russian. Letters are dictated in whatever language the addressees speak: Russian, German, French, English, Spanish.

Because Trotsky has written so voluminously, I had the impression that he composed rapidly. However, he not only dictates slowly but works over the typed copy many times. After the transcript is handed to him for correction, he introduces so many changes that it is often hard to recognize the original. What was originally a page may, when it returns to the secretary for retyping, be four times as long.

While the “collaborator”—so he calls his secretary—is making neat copies and dividing the “page” into four numbered ones, Trotsky strides in and out of the room and again adds and subtracts. The greater length of the final copy, as compared with the original, results not so much from polishing as from expansion of content.

Trotsky does not work from a written outline. What he dictates is the first “draft” of his thoughts. I found that the first dictation is often more florid than the final text, in which he mercilessly cuts adjectives not absolutely essential. Precision of expression is what he strives for, and the final text expresses his thoughts most tersely.

In measured steps L.D. paces up and down the study while he dictates, weighing each word. But there is nothing phlegmatic in this slow dictation. His low, calm tone only emphasizes the limitations that exile imposes on a man of such dynamic energy. The beauty of the Russian language is enhanced by the eloquence of a master orator. There is no vanquishing the verve and sweep in his compositions, which expound the cause of world revolution.

During dictation Trotsky sometimes stops to examine his library—long, plain shelves lined with the writings of Marx, Engels, and Lenin; his own works; reports of the congresses of the Communist International; works on economics, science, philosophy, psychoanalysis; and below these, books of fiction, mostly in French.

Trotsky is not only familiar with the contents of each book but the exact place it occupies on the shelves. He is quick to note any change in arrangement, any new bindings, or—calamity!—a missing volume. At other times his eyes gaze into the patio, where strange primitive stone idols stand, grimly oblivious to the pungency of jasmine, roses, and oranges; on the high walls over which bougainvillea climb; upon the horizon and beyond.

My first experience with the press began at the close of my first day’s work. An interviewer had been granted an audience—a correspondent for a leading New York daily.

As a rule, journalists were granted the courtesy of interviewing Trotsky in his study. But that night Diego and Frida Rivera were spending the evening with L.D. and Natalia Ivanovna, and thus Trotsky merely saw the reporter in my workroom.

When the reporter came, I gave him written answers to his written questions. He read them in my presence and signed a statement to the effect that these answers would be published in full and exactly as written. Trotsky entered and I introduced them.

I found the interview interesting to watch, and now, in light of subsequent events, I cannot help but smile at the memory of it. Both in appearance and manner the correspondent was a little man. He seemed to melt out of sight the moment the former War Commissar entered the room.

Overwhelmed, he dared no more than ask for Trotsky’s approbation: “Did Mr. Trotsky like his questions?”

Trotsky smiled: “I answered them to the best of my ability.”

The gentleman of the press looked foolish. At the conclusion of their ten-minute conversation, he praised the “brilliant clarity” of Trotsky’s answers and begged forgiveness for being sentimental: “But it would mean a lot to me if I could have Mr. Trotsky’s autograph.”

Trotsky appended his signature to the statement and returned to the Riveras. The reporter was escorted out through the other side of the patio. He was later to present this—not in the New York daily for which the interview was intended, but in a lurid Chicago monthly—as proof that Leon Trotsky and Diego Rivera were not on speaking terms!

That same correspondent did not stop with this figment of the imagination but so quoted Trotsky as to give his statements a peculiar, unreal twist. He achieved this by breaking up the quotations with his own interpolations. This also created the impression that the answers had been given orally and that the author of the article had had a lengthy session with Trotsky instead of a mere ten minutes.

There is no way to judge whether the actions of the New York (or Chicago?) reporter were hypocritical while he spoke with Trotsky, or whether he chose to forget what had occurred when it came to marketing his wares. Perhaps I have tarried too long on this point, but such reporting is typical of how interviews with Trotsky are enacted and how they are prepared for public consumption. The knowledge of this tore away the flimsy fabric of the descriptions of Trotsky I had previously read.

In December of last year the press reported that Trotsky and his staff were “vacationing.” While we were driving out to the country, Trotsky asked if I could take dictation in the forest—on my lap. I was about to say yes when a gentle kick from Natalia reminded me that we were, after all, on vacation, and that the proper answer should be “No.”

Even this negative answer, which L.D. accepted, did not keep him from writing part of each day. When our two-week vacation ended, Trotsky had dictated three articles, some twenty pages each, on widely different topics: *Spain—The Last Warning*; *Behind the Ramparts of the Kremlin*; and an introduction to Harold R. Isaacs’s *The Tragedy of the Chinese Revolution*.

Not having brought all our office supplies, we had no sponge. One morning I was licking the flap of an envelope prior to sealing it. At that moment L.D. came into the room, looked in astonishment at the contortions of my tongue, and exclaimed, “What savagery!”

I watched his now-familiar vigorous stride as he walked out. According to his high hygienic standards, licking an envelope was nothing less than barbaric. But he felt he had been too brusque. When Trotsky has occasion to be harsh with any of us, he is immediately contrite and seeks a basis for rapprochement.

Within fifteen minutes he returned with a large bouquet of flowers he had picked himself. Gratefully, I concluded our rapprochement.

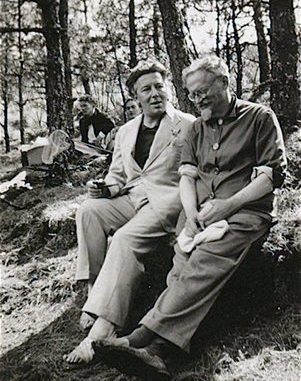

The Riveras arrived in the country and joined us in a hike through the woods. L.D., however, was skeptical about Diego remaining with us throughout the morning. Diego protested that he wished to hike and did not want to paint. L.D. said, “Yes, yes, Diego. You will be with us—provided you do not meet a tree.”

Diego Rivera did “meet a tree,” and he and his easel sat down. We did not see either of them until twilight.

We were forced to return to Coyoacán earlier than planned, having received information that an attempt was being prepared on Trotsky’s life. (Walter Krivitsky, who had refused to return to Russia during the wholesale recall of the diplomatic staff, had so informed Trotsky’s son in Paris, Leon Sedov.)

The GPU had increased its activity in Mexico by importing two professional cutthroats: a French agent responsible for the murder in Lausanne of Ignace Reiss (an important GPU agent who had broken with Moscow and joined the Trotskyist Fourth International), and a petty thug from Philadelphia who, while in charge of the GPU in Spain, had been instrumental in causing the “disappearance” of Trotsky’s Czechoslovakian secretary, Erwin Wolf.

The murderous hand of the Stalinist GPU then extended to France, where it perpetrated the gruesome murder—his body found headless and legless in the Seine—of another of Trotsky’s former secretaries, the young German refugee Rudolf Klement.

We had been sent a picture of these two members of the international Mafia. One of the guards suggested we use it in our target practice. Not only could there be no laxity in our vigilance, but extra precautions had to be introduced. I now understood the necessity of the heavy guarding and no longer felt ill at ease in our fortress.

The vacation over, the working day was normalized. During the day we had a one-hour rest period. L.D. spends his rest period reading newspapers—foreign ones such as Le Temps, The New York Times, Pravda, The Manchester Guardian —as well as the local press.

Trotsky has an elaborate system of underscoring articles he deems important: neat lead-pencil marks, blue and red lines, and once in a while a remark, usually in Russian, at the side of a paragraph. When we file the papers—which require an entire room—we carefully examine the underlined articles. In addition to geographical and chronological files, we maintain a special subject file of important articles.

When work resumes after the siesta, it continues until 7 p.m., when we dine. After dinner Trotsky again reads—magazines and books—and most of us follow suit in our rooms.

I became absorbed in reading Trotsky’s Russian works that had never been translated into English. The particular volume, *Science and Revolution*, held my attention. It contained a speech delivered to a chemical society entitled “Mendeleyev and Marxism.” I decided to translate it because it revealed a side of Trotsky not generally known to the public, who consider him merely a “politician.”

The circumstances under which the speech was given reveal the man. In 1925, when the Stalinist bureaucracy had already begun its fight against him, Trotsky resigned as People’s Commissar of War. To embarrass him, the bureaucracy assigned him posts unrelated to each other and wholly unfamiliar: chairmanship of the technico-scientific board of industry. He thus found himself in charge of scientific institutions.

In that capacity he addressed the Mendeleyev Congress on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the Academy of Sciences. Though he considered himself an amateur in the field, the lecture is remarkable for its profound evaluation of the relationship between science and historical trends.

It is interspersed with characteristic flashes of humour: “Chemistry is a school for revolutionary thought not because of the existence of a chemistry of explosives—explosives are far from always being revolutionary—but because chemistry is first of all a science of the conversion of elements, and thus is dangerous to every kind of absolute or conservative thinking, cast in immobile categories.” Referring to Darwin’s naïve attempt to transfer the conclusions of biology into society, Trotsky said: “To interpret competition as a ‘variety’ of the biological struggle for existence is the same as to see only mechanics in the physiology of mating.”

Having translated the speech on my own initiative, I was anxious to make a good impression and carefully compared the English with the Russian text. I then asked Trotsky’s opinion without showing him the original.

When he returned the manuscript, he indicated one place and said a sentence had been left out. I was astounded. Was it possible that he recalled so well a speech made thirteen years earlier, on a subject in which he was an “amateur,” that he remembered a sentence omitted in translation? I had heard of Trotsky’s phenomenal memory but was sceptical.

He said in his defence, “I do not remember exactly the statement, but I think this is it…” and dictated the sentence. Upon rechecking, I found it to be exactly as in the original.

The whole life of this affable, hardworking family was suddenly changed. From Paris came the news of the untimely death, under mysterious circumstances, of the eldest son of Leon Trotsky and Natalia Sedova. Leon Sedov had been their only child who had hitherto escaped the clutches of the GPU.

When Trotsky and Natalia were exiled in 1927, their younger son Sergei—a brilliant engineer—remained in Russia. He believed that his lack of interest in politics would guarantee his ability to serve the Soviet Union without persecution. But he was arrested and has now “disappeared.”

Zina, Trotsky’s eldest daughter by his first wife, Alexandra Lvovna Sokolovskaya (herself in exile in Siberia because of “Trotskyism”), committed suicide when Stalin, after granting her permission to leave the country for medical treatment in Berlin, vengefully refused her a visa to return to her home, husband, and children.

Yagoda, Yezhov’s predecessor as head of the GPU, had driven Trotsky’s younger daughter Nina to a premature death.

The death now of Leon Sedov inflicted the deepest wound—and in the most vulnerable spot. It came like the insidiously planned feat of a master intriguer. Leon Davidovich and Natalia Ivanovna locked themselves in their room and welcomed no one.

For a week they did not emerge. Only one person was admitted—the maid, who brought them mail and food, of which they took little.

Those were dismal days for the entire household. We did not see either L.D. or Natalia. We did not know how they fared and feared the consequences of the tragedy upon them. We moved typewriters, telephones, even doorbells to the guardhouse, out of sound of their room. Their part of the house became deathly quiet. An oppressive air hung over us, as if the whole mountain chain of Mexico were pressing down upon the house.

The blow was harder not only because Leon Sedov had been their only living child but because he had been Trotsky’s closest literary and political collaborator. When Trotsky was interned in Norway, gagged, unable to answer the monstrous charges levelled against him in the first Moscow Trial (August 1936), Sedov had penned *The Red Book*, which, by brilliantly exposing the Moscow falsifiers, dealt an irreparable blow to the prestige of the GPU.

In the dark days after the tragic news reached us, when L.D. and Natalia were closeted in their room, Trotsky wrote the story of their son’s brief life. It was the first time since pre-revolutionary days that Trotsky had written by hand.

On the eighth day Trotsky emerged. I was petrified at the sight of him. The neat, meticulous Trotsky had not shaved for a week. His face was deeply lined; his eyes were swollen from too much crying. Without a word he handed me the handwritten manuscript, Leon Sedov: Son, Friend, Fighter, which contained some of his most poignant writing.

Knowing Trotsky as I did, I knew every word, every comma had meaning, and that each word ultimately chosen was the most meager he could find to express the profoundest sorrow:

“Together with our boy has died everything that still remained young within us.”

But even this great grief did not dim Trotsky’s ardor for the revolutionary cause. The pamphlet was dedicated “to the proletarian youth.”

It ended with the appeal:

“Revolutionary youth of all countries! Accept from us the memory of our Leon, adopt him as your son—he is worthy of it—and let him henceforth participate invisibly in your battles, since destiny has denied him the happiness of participating in your final victory.”

Though Trotsky has a strong physique, he suffers from a peculiar ailment that saps much of his energy and often keeps him confined to bed. The new sorrow brought on a recurrence of his illness. A complete rest was prescribed.

The next morning the papers announced the Third Moscow Trial (March 1938), scheduled to open within two short weeks of Sedov’s death. Was this coincidence? We, who knew the GPU had dogged Sedov’s steps for years, believed otherwise.

Had not the memory—and circulation—of *The Red Book* so stung the GPU that they wished to rid themselves of this valiant fighter before staging the new “Trials”? Had they not hoped that the tragedy would stun Trotsky, rendering him incapable of answering the fresh accusations?

If so, they underestimated their opponent. No personal tragedy could daunt Trotsky when the task of exposing the greatest frame-up in history cried for accomplishment.

It was a joy to have Trotsky working with us again and to note the speed, accuracy, perseverance, and unflagging energy of this modern Prometheus.

Trotsky laboured late into the night. One day he was up at 7 a.m. and wrote until midnight; the next he arose at 8 a.m. and worked straight through until 3 a.m. the following morning. The last day of that week he did not sleep until five. He drove himself harder than any of his staff.

Trotsky wrote an average of 2,000 words a day. He gave statements to NANA, UP, AP, Havas, the *London Daily Express*, and the Mexican newspapers. His declarations were also issued in Russian and German. The material was dictated in Russian. While I transcribed, the other secretaries checked every date, name, and place mentioned in the trials.

Trotsky demanded meticulous, objective research. The accusers had to be turned into the accused.

Trotsky at no time allowed the subjective factor into his analysis of the “confessions.” He was deeply incensed when the papers printed rumours that Stalin had never been a revolutionist but had always been an agent of the Tsar and was merely wreaking vengeance.

When I brought him the newspapers carrying this explanation of the purge, he exclaimed: “But Stalin was a revolutionist.”

“Wait a moment,” he called as I left the room. “We’ll add a postscript to today’s article.”

He dictated:

“The news has been widely spread through the press to the effect that Stalin supposedly was an agent provocateur during Tsarist days, and that he is now avenging himself upon his old enemies. I place no trust whatsoever in this gossip. From his youth Stalin was a revolutionist. *All* the facts about his life bear witness to this. To reconstruct the biography ex post facto means to ape the present Stalin, who from a revolutionist became the leader of the reactionary bureaucracy.”

To us, the trials did not lack a humorous angle. The chimerical accusation that Trotsky earned a million dollars as an “agent of Hitler” seemed a monstrous joke at the expense of a household that is perennially broke. Trotsky’s literary earnings—and they are by no means fabulous—support us all.

L.D. himself is completely unaware of his material surroundings. I believe comforts would distract him. Once he overheard Natalia and me discussing the purchase of a soft chair for him. (The chairs in his study are all plain wood.) He was shocked at the idea of such a “luxury.” Moreover, he said, he did not like soft chairs; those he had were best for working.

It is not only that the furnishings are unpretentious; it is that often we do not have enough money for the simplest necessities. During the trials we were forced to cut eggs and butter from breakfast and meat from dinner.

This “million” amused us.

Imitating Trotsky’s military stride, I burst into the kitchen. There stood diminutive, charming Natalia Ivanovna. In her quiet, efficient way of doing her work—whether writing his diary (Trotsky drew liberally from it for his autobiography), assisting us in research, controlling the purse strings, or managing the kitchen—she is indispensable, though inconspicuous.

With utmost seriousness I demanded two eggs and buttered toast for breakfast. Natalia looked perplexed. She thought it reasonable that I should have breakfast instead of merely cereal (“mush,” we called it), a roll, and coffee. But until money arrived for yesterday’s article, she could not promise it. The London paper had promised to cable the funds that very day.

“But,” I insisted, “why wait for that money when Trotsky has ‘earned a million’?”

“Oh,” she said, greatly relieved, “those *negodyai*—scoundrels.”

After all the strictly political articles I had been typing, it was a delight to hear such a simple expression about the well-fed Thermidorians entrenched in the Kremlin.

Trotsky’s phenomenal memory was of great assistance, not only in his extraordinary political analysis, but to his secretarial staff, who searched for old documents, as some ludicrous charges dated back to 1919, when Trotsky was in power and Stalin a nonentity.

Credit, of course, should also be accorded the Kremlin slanderers, who assisted us greatly by repeating dates and places already refuted in the first two trials (August 1936 and January 1937).

It had taken Moscow over a year to build the new frame-up and inquisitorially extract the latest “confessions,” but Trotsky had to demolish the calumny as fast as the press reported each session.

Even during this trying week, Trotsky’s infectious optimism inspired us all. Asked whether pessimistic conclusions about socialism followed from the trials and the verdict of the Commission, Trotsky replied:

“No. I see no basis for pessimism. It is necessary to take history as it is. Humanity moves forward as did some pilgrims: two steps ahead, one step back. During the backward movement all seems lost to skeptics and pessimists. But this is an error of historical vision. Nothing is lost. Humanity has developed from the ape to the Comintern. It will advance from the Comintern to actual socialism. The judgment of the Commission demonstrates once more that the correct idea is stronger than the most powerful police force. In this conviction lies the unshakable basis of revolutionary optimism.”

The week of the trials ended. The secretarial staff was ready to rest.

But L.D. announced that he would now resume work on the life of Lenin, which he had been forced to abandon in Norway, and would simultaneously write a biography of Stalin—a sociological and psychological study of the man who “from a revolutionary became the leader of a reactionary bureaucracy.”

L.D. emphasized how glad he was that no more of his time need be spent exposing frame-ups. Now he could devote himself to “real work.” We marveled at his energy. He was fifty-nine, in exile, and had just suffered the death of his son.

“I told Natalia of the death of our son—in the same month of February in which, thirty-two years earlier, she brought to me in jail the news of his birth. Thus, ended for us the day of February 16, the blackest day of our personal lives.”

We of the younger generation were exhausted by the week’s speed and strain and thought we deserved laurel wreaths for our accomplishments. But to the indefatigable Trotsky it had been merely something that took precious time from his major literary works.

When asked whether he thought his personal fate pathetic, Trotsky firmly replied no. He did not view the world from a personal standpoint; history was the tide, and one had to know how to swim against the current as well as with it.

His whole life illustrated his point. He had entered the revolutionary movement at eighteen; for participating in a strike he was arrested and exiled. Lev Davidovich Bronstein assumed the name of his jail guard, Trotsky, and made an audacious escape from Siberia.

At twenty-six, in 1905, he tore up the Tsar’s manifesto and became president of the first Petersburg Soviet of Workers’ and Peasants’ Deputies. The reaction that followed the failure of that revolution demoralized many an old revolutionist, but to the young Trotsky imprisonment and exile were periods of “leisure” in which to hammer out the theory of “permanent revolution,” which would assure the success of the next revolution.

1905 was merely a “dress rehearsal” for the Revolution of 1917, which, with Lenin, he led successfully.

When the failure of revolution in other countries created fertile soil for bureaucratization in Russia, Trotsky continued his Spartan way of living and fought against the bureaucracy. When Stalin—whom Trotsky had called the “organizer of defeats”—rode into power on a wave of defeats and Trotsky found himself an exile for the third time (the Tsar had exiled him twice), he turned to his remaining weapon: the pen. Yes, Trotsky could swim against the current.

We knew these events in Trotsky’s life, and their recapitulation helped us understand the Trotsky of today. Still we wondered: did he miss his life in power?

But Trotsky drew no line of demarcation between his life in exile and his life in power. It was theory, he maintained, which answered the desires of the masses for freedom, which inspired them with the will to power—and with the will to power came the weapons. And it is the word of class truth that will again turn the tide.

I could not participate in the meticulous research for the life of Stalin, for word reached me of my father’s death. I decided to return to the States.

When I arrived in New York, I heard that another tragedy had struck my family: my brother had met death in an automobile accident. I immediately went to Chicago, where my mother then was. There a letter from Trotsky awaited me.

“Dear Rae,” the handwritten Russian note said, “Natalia and I were shaken by the news of your brother. What can one say? … Two blows fall upon your family in so short a time. Your mother is especially to be pitied; for her it is hardest of all.

Dear Rae, we wish you strength and courage in face of it all. Natalia and I express our warmest, most sincere sympathy to all members of your family, and you, dear Rae, we firmly embrace.

Yours, L.D.”

Even my mother, a religious woman to whom Trotsky is merely an “infidel,” could not help being moved. “How,” she asked, “can a great man like that be so simple?”

“It is his simplicity which makes him great,” I answered. And yet it is a trait the world has overlooked in Trotsky. I, too, had once been wary of his “egotism,” his “coldness.” Though his greatness had inspired me to work for him, I feared his “dictatorial” methods. But his simplicity quickly dissipated that impression.

We—his secretariat—felt uncomfortable when he referred to us as his “collaborators.” We appreciated the magnanimity but considered the appellation fantastically exaggerated. Yet he meant it genuinely. He never regarded us as people who worked “for” him; he considered us members of his family who assisted him in his literary creations.

I know the simple, personal traits in Trotsky. They do not detract from his greatness—they make him human.

It is his simplicity, his devotion to one cause throughout his life, his fervent belief that the revolution which began in Russia is but a link in the “permanent revolution,” the world socialist revolution, that makes of him now a lone exile—but a power.