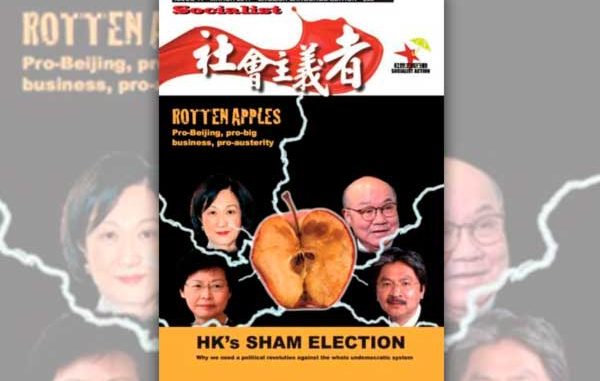

Pan-democrats sink to new low by supporting “lesser evil” John Tsang.

Hong Kong’s Chief Executive election is a five-yearly political farce. It has been described as the world’s most bizarre election. Just 1,194 electors in the elite Election Committee will cast their votes on 26 March. That’s 0.03 percent of the territory’s eligible voters. The majority in this ‘small circle’ election system are billionaires and millionaires. Li Ka-shing, Hong Kong’s richest man, wields ten votes in the committee through the allocation of votes to his company, CK Hutchison Holdings. This monstrosity of an electoral system, blatantly favouring the capitalist elite, is used by the Chinese dictatorship to keep control over Hong Kong. But it is a ticking bomb that enrages growing numbers of people.

To generate some popular support for the system and the government that issues from it, there is intensive media coverage. Like a TV reality show, the establishment’s spin doctors try to capture public interest and build a connection between the mass of disenfranchised Hong Kongers and the contestants, all but one of whom will be eliminated by the ‘judges’.

Lam vs Tsang

The dictatorship’s favoured choice this time around is Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor who in her role as Chief Secretary was the main sidekick of outgoing leader Leung Chun-ying (‘CY’). This has earned her the name ‘CY 2.0’. Her former boss was barred by Beijing from standing for a second term because of a succession of political crises since he came to power in 2012: the biggest protests in Hong Kong’s history in 2014 (Umbrella Movement), an upsurge in support for Hong Kong independence (17.4 percent in a poll last year), and an unprecedented anti-establishment mood as reflected in September’s legislative elections.

Beijing saw the need for a change of face at the top in order to gain a breathing space, but it shows no signs of a change of direction. More repression and tighter mainland control is still the order of the day, meaning ‘CY Leungism without CY’. Lam is seen by Beijing as the best candidate to facilitate this agenda.

In total there are three other candidates, but Lam’s main challenger is former Finance Secretary, John Tsang Chun-wah, who has molded himself as a more tolerant, inclusive and local alternative. The conflict between Lam and Tsang mainly reflects the split within the capitalist class into two camps, with Tsang closer to the traditional Hong Kong tycoons who have lost ground to mainland business interests under CY’s rule.

Tsang’s campaign image is misleading. He has run Hong Kong’s economic policy for the past nine years as a loyal tool of the Chinese regime. His budgets earned him the monicker ‘Scrooge’ – keeping a lid on welfare spending while shifting public funds into white elephant infrastructure deals that make the capitalist tycoons even wealthier.

Tsang bears as much responsibility as anyone for Hong Kong’s galloping wealth inequality. The number of ‘working poor’ families rose 10 percent from 2010 to 2015 with Tsang at the Finance Ministry. He opposes a universal pension system and other crucial anti-poverty measures.

Article 23

Like Lam, Tsang is no democrat. He recently shocked supporters (those gullible enough to buy his “softer” image) by saying he would introduce Article 23 national security legislation during his first term as Chief Executive. This is legislation that would severely curtail the right to protest and the possibility to criticise the Chinese dictatorship.

Despite the similarity of the candidates, the Chinese regime is furiously lobbying for Lam. This is mostly about the struggle between the two camps within the capitalist class. Beijing is under pressure to favour mainland interests, but also wants to hide this split by securing the biggest possible margin of victory for the winner. It doesn’t want the next administration being seen as weak and divided. It sorely needs a ‘success’ for its fraudulent election system.

A senior official, Wang Guangya of China’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, recently stated that the central government is “unanimously” behind Lam. Former Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa has even implied Tsang would not be approved (i.e. disqualified) by Beijing if he won. Such statements are designed to ‘whip’ the committee’s pro-establishment majority into line.

But the biggest story of this election is the shameful shift of position by the leaders of the pan-democratic bloc who in most cases are backing Tsang as the “lesser evil”. The pan-democrats have a bigger vote in the committee than in previous years – 326 of 1,194 seats – but are determined to use this ‘power’ to shore up the house, rather than to bring it down.

One of the few prominent voices who has taken a principled stand and exposed this disastrous position is ‘Long Hair’ Leung Kwok-hung who has attacked Tsang’s political record and criticised the pan-democrats for “idolising Tsang as Hong Kong’s only hope”. Long Hair also attempted to launch a campaign to get 38,000 public nominations (1 percent of the total voting population) to use this as a counterweight to the pan-democrats’ increasingly blatant pro-Tsang campaign. Socialist Action actively took part in support of Long Hair.

In late February, having collected 20,000 names in two weeks, he called off his campaign fearing it would not reach the target level of nominations (which only have political weight, with no legal validity in the rigged election mechanism). Behind the scenes, the pan-democratic leaders have pulled all possible levers to undermine Long Hair’s campaign. Still, Socialist Action believes the decision to cancel was mistaken. By far the best course would have been to continue to get nominations for Long Hair from ordinary citizens, using this to agitate among the public against the sham election and the pro-Tsang pan-democrats.

Long Hair’s campaign was frustrated rather than helped by the online polling initiative launched by former ‘Occupy Central’ mastermind Benny Tai Yiu-ting – a project which repeatedly broke down due to technical and privacy problems. Tai’s ‘Civil Referendum 2017’ automatically included all the establishment candidates (even Woo Kwok-hing who explicitly asked to be excluded), turning this into a ‘neutral’ opinion poll exercise rather than having any value as part of the political struggle against the system.

Political desperation

In previous small circle elections the ‘moderate’ pan-democrats put up their own candidates (Alan Leong Kah-kit in 2007 and Albert Ho Chun-yan in 2012). Even that was at odds with wide layers of the democracy movement who correctly stood for a boycott and accused the pan-democrats of legitimising a rigged election. This time, the ‘moderate’ pan-democrats have gone one step further, not even bothering to field their own token candidate but instead backing a politician outside and opposed to the democracy struggle.

In a display of political desperation on their part, 125 of Tsang’s 160 nominations have come from pan-democrats. This not only legitimises the ‘small circle’ farce but also legitimises the choice of candidates dictated by Beijing’s rules (to exclude pan-democrats). In other words, it legitimises Beijing’s screening principle, which is the crux issue over which the 2014 Umbrella Movement exploded.

Mass struggle

These ‘leaders’ have always sought to lower political consciousness and build illusions in the possibility to reform the current undemocratic system, such is their fear of mass struggle which is the only way to change the system. This replicates their role in holding back mass protests against the government in 2014 (the Umbrella Movement broke out despite them) and the rotten (and secret) deal on political reform in 2010 between the leaders of the Democratic Party and the Chinese regime.

The latest slide by the pan-democratic leaders into the swamp of compromise, means further rotten deals could be posed under the next government. This is more likely in the unlikely event Tsang should win, but it isn’t excluded even under Lam. Prominent figures in the Democratic Party, such as James To Kun-sun, have flagged for new political u-turns saying they could accept a version of Article 23, and also the ‘831 ruling’ as the basis for a new round of political reform. The August 31, 2014, ruling by China’s NPC Standing Committee for a screened Iran-style election system, was the spark for the Umbrella Movement.

These developments underline the urgent need to rebuild the democracy struggle as a fighting movement with genuine internal democracy and grassroots control. The compromise manoeuvres of the pan-democratic tops do not reflect the real mood in society, as shown by September’s Legco elections (open to ordinary voters) when candidates seen as more ‘radical’, albeit on a variety of sometimes very confused platforms, gained over 25 percent of the vote – at the expense of both the pro-government camp and the pan-democrats. The key component of a successful strategy to defeat the dictatorship and win real democracy is a new working class party with socialist policies to smash the economic and political stranglehold of the tycoons.

Be the first to comment