Following a decade of recession and austerity, and as the profit system wreaks havoc with lives and livelihoods during the Covid-19 pandemic, more of the left and trade union movement in Britain and internationally are turning towards cooperatives as a way to save ailing firms and jobs.

On a broader level, some argue that cooperatives are a possible alternative to the domination of global capitalism.

It seems all wings of the labour and trade union movement have renewed interest in cooperatives. During Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the British Labour Party cooperatives were given considerable emphasis in a document looking at an ‘alternative model’ to capitalism. The party’s 2019 election manifesto promised a significant expansion of cooperatives.

Richard Wolff, “America’s most prominent Marxist economist” (New York Times Magazine), advocates ‘workers’ self-directed enterprises’, as the way towards ‘economic democracy’ for the working class. At the other end of the spectrum, Sir Keir Starmer, British Labour Party leader and a keynote speaker at the recent conference of the Cooperative Party (which is affiliated to Labour), advocates the ‘Co-op Councils model’, which are described as “a network of over 30 Labour councils piloting models of service-user or community control”.

The International Cooperative Alliance, formed 125 years ago, defines a cooperative as “an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise”.

According to the World Cooperative Monitor (2019), more than 12% of humanity (over one billion people) are part of any of the three million cooperatives in the world. The largest 300 cooperatives employ 280 million people across the globe (10% of the world’s employed population).

The UK has a diverse co-operative movement, involving over 7,100 co-ops, ranging from local shops, football supporters’ trusts and credit unions to Woodcraft Folk, worth £37.7 billion to the economy. A recent addition, Student Cooperative Homes, aims to provide “permanently affordable homes formed by students who democratically manage the property they live in”.

In Europe, three countries, Finland, Ireland and Austria, have over half of the population in cooperative membership. In Africa, one in 13 people are members of a cooperative. Countries with the highest proportions of populations in cooperative ownership include India (242 million) and the USA (120 million).

There is no doubt that many cooperatives have played a positive role, improving the conditions and lives of millions of working-class people and the rural poor, fostering solidarity and a collective approach. This is a sharp contrast to the boss’s exploitation and alienation and greed that are all intrinsic to capitalism. But do co-ops represent ‘bottom-up socialism’, as some argue? Can they grow to become a viable alternative to capitalism, on a national and global scale?

Early cooperators

These are very old debates. The cooperative movement finds its origins with ‘Utopian socialists’ like Comte de Saint-Simon and Charles Fourier, in France, and Robert Owen, in Britain. In revulsion at the horrors of the industrial revolution, they attempted to draw up plans for how society could be better organised.

They believed that rational argument, producers’ cooperative models, and gradual reform would be more efficient than capitalism. Owen postulated that producers’ cooperatives would gradually spread, leading to a classless communist society. He established the New Lanark community in Scotland, which included a factory, homes and a school.

Another titan of the cooperative movement, William Thompson, drew on Owen’s ideas for plans for a cooperative community in his native Ireland but he disagreed with Owen’s paternalistic approach and courtship of rich and powerful patrons.

Thompson argued for democratically organised and run communities, suited to the limited resources of the largely working-class cooperative movement, and for workers eventually securing ownership of the community’s land and property. But this approach did not solve the persistent problem of the scale of production and the coercive role of the capitalist state.

Thompson’s detailed plans for cooperative communities were sharply contested with Owen at the Cooperative Congresses held in the 1830s and formally adopted by the Third Congress, in 1833. By now, cooperators also now called themselves ‘Owenites’ and ‘Socialists’, and Thompson’s radical democratic methods and opinions drew strong support from the grassroots.

Thompson died later in 1833, and Owen was reluctant to try to form new communities in the 1830s. From then onwards in Britain, the cooperative movement grew mainly in the form of trading and consumer businesses, rather than in entire self-governing communities. This tended to blunt the movement’s radical democratic and socialist-communist aspects. These decades also saw the rise of the Chartists and burgeoning trade unions, many of whose activists and leaders had been ‘cooperators’ and were greatly influenced by Owen and the radical ideas of Thompson.

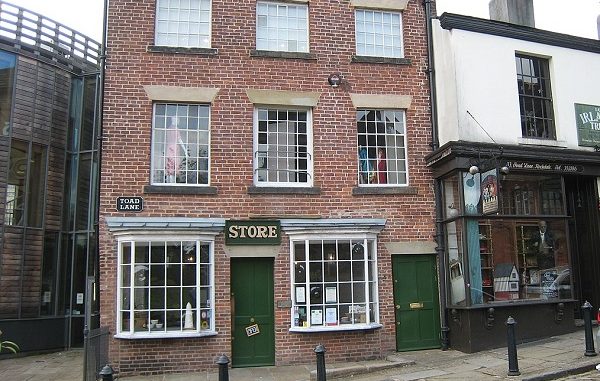

The modern cooperative movement in Britain considers the ‘Rochdale Pioneers’ as its prototype. In 1844, a group of 28 artisans, working in the cotton mills in Rochdale, established the first modern cooperative business by pooling their scarce resources to access basic goods at a lower price.

Similar cooperatives were formed across Britain and began to spread internationally. By the early 1860s, there were over 250 retail co-ops in Britain, and by 1864 a co-op store operated in Africa.

Marx and Engels

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the founders of scientific socialism, were enthusiastic about the emergence of producers’ cooperatives. They admired Owen despite the flaws of his ideas. Thompson’s writings on the nature of exploitation in the capitalist economy (“surplus value”) were cited by Marx in Capital.

Writing for the International Workingmen’s Association (IWMA), in 1864, Marx and Engels said of cooperatives: “The value of these great social experiments cannot be overrated. By deed instead of argument, they have shown that production on a large scale, and in accord with the behests of modern science, may be carried on without the existence of a class of masters employing a class of hands…”

Today, some advocates of cooperatives argue that a ‘cooperative socialism’ can emerge from the growth of co-ops. This echoes the ‘revisionist’ ideas of the German socialist, Eduard Bernstein, in the late 19th century. He argued that the spread of trade unions and cooperatives was proof that capitalism was slowly evolving towards full democracy and socialism, from within, and that revolutionary socialism was not needed.

But Marx and Engels had already described the limitations of cooperatives, which were restricted in scale and by “individual wage slaves’ private efforts”. This meant that “the co-operative system will never transform capitalist society. To convert social production into one large and harmonious system of free and co-operative labour, general social changes are wanted, changes of the general conditions of society, never to be realised save by the transfer of the organised forces of society, viz., the state power, from capitalists and landlords to the producers themselves” (IWMA, 1866).

Marx and Engels shared Fourier and Owen’s hatred of exploitation and capitalism, and their “imaginative expression of a new world”. But they rejected the naive belief that the rich would voluntarily surrender their wealth and power.

The cooperative movement cannot just grow within capitalism and eventually take over. The bosses would ruthlessly utilise their economic, political and state might to crush any alternative movement that threatened the capitalist mode of production (Just look at how they dealt with Jeremy Corbyn’s relatively mild left-reformist programme).

Marx and Engels argued that only a revolution that mobilised millions could overthrow the capitalist state, dispossess the property-owning classes, and construct a new socialist society based on genuine democracy, equality and cooperation.

Rochdale Pioneers

The ‘Rochdale principles’ state that “cooperatives are democratic organisations controlled by their members, who actively participate in setting their policies and making decisions.” Compared to a capitalist workplace, the benefits of modern-day coops are, at least on paper, obvious. A worker-co-op replaces the capitalist with a democratic association of workers, and the workers control their own immediate work and share and invest profits in a cooperative manner.

Forms of co-operatives, such as the consumer (food, housing), producer (agriculture) and worker-owned and managed (products and services) sectors, can show the potential and material benefit of coops. They can pose questions about an alternative to the capitalist system.

But, as Marx pointed out, co-ops cannot operate independently of the capitalist system: “The co-operative factories of the labourers themselves represent within the old form the first sprouts of the new, although they naturally reproduce, and must reproduce, everywhere in their actual organisation all the shortcomings of the prevailing system” (Capital, Vol.3).

These “shortcomings” include the pressures of competition and marketing in a profit-driven market economy; to cut costs, skimp on quality, hold back wages and the number of employees and so on. Co-ops may be cooperatively and democratically run, but they exist in the capitalist market and are governed by the ‘logic’ of market competition.

As a cooperative grows bigger and its operations more complex, there is relentless pressure to find capital for development, to ‘professionalise’ the management, and to find ways to skirt around cooperative members’ democracy and participation.

In the 2000s, the UK Cooperative Bank imitated its private rivals and recklessly expanded. In 2014, overburdened with buyouts, the Co-op Bank was forced to demutualise, seeking private capital to keep afloat.

The Co-op Group, the parent body of the bank and many other retail and services, was badly exposed and suffered huge financial losses. For a time, the very future of the Co-op Group seemed in doubt.

Since 2017, the Co-op Bank has been 100% owned by a group of hedge funds and private equity firms. Last August, the bank announced that it will cut 350 jobs and close 18 branches, blaming low-interest rates and the Covid-19 crisis.

In a worrying sign, the Co-op Group announced that from 2021 it will cease funding of the ‘Co-op News’ print journal (founded in 1871) and stop “providing other unrestricted funding to Co-op Press”. Yet, at the same time, the Group can find up to £100 million on a 15-year ‘sponsorship’ deal with the Oak View Group, for the ‘naming rights’ to the developer’s planned 23,500-capacity arena in Manchester.

Mondragon

The Mondragon Cooperative Corporation, the world’s largest federation of worker cooperatives, which originated in the Basque country, in 1956, is another case in point. Recently, Mondragon was included in Fortune Magazine’s list of “enterprises that are changing the world”. Fortune praised Mondragon for being a “financially sound business while putting people before profit.”

However, a few years ago, Mondragon ran into serious problems. As the cooperative grew from the 1960s onwards, it gradually changed many of its initial goals in an effort to compete and develop ‘economies of scale’ in a competitive capitalist world.

In order to get managers with specific skills, Mondragon hired from outside firms and had to pay competitively. The one-worker/one-share/one-vote rule, common to many co-ops, also changed at Mondragon, leading to economic inequities in the co-op.

Mondragon co-ops started to hire outside non-member workers with neither secure employment, co-op benefits, or decision-making power. The co-op corporation also invested in financial sector ‘products’, such as hedge funds.

These changes came home to roost in 2008, during the global financial crisis. Fagor, the Mondragon ‘flagship enterprise’, employing 5,642 workers at 13 manufacturing plants in five countries, was forced into bankruptcy after over-extending itself. Thousands of members were laid off, and non-co-op members were sacked, without any benefits.

Mondragon argued that it did attempt to save as many members’ jobs and co-ops, as possible, relocated Fagor jobs to other co-ops, and has not jettisoned all of its co-op principles. But the partial collapse brought home the degree to which capitalist relations were able to penetrate Mondragon, and its increasing reliance on the financialised neoliberal model of capitalism.

Workers’ cooperatives

Cooperatives tend to become more popular during periods of capitalist crisis and as the profit system’s institutions and ideology lose authority. As we enter depressed economic conditions arising from the market system’s calamitous response to Covid, thousands of firms, big and small, will fail. In some cases, turning them into workers’ cooperatives will be posed, where employees see no other alternative to save jobs. Socialists are sympathetic to these initiatives but the lessons of previous attempts need to be studied by the workers’ movement.

After the economic collapse of Argentina in the early 2000s, many workers took over their factories and formed co-ops. But after a while, many of these were consumed by the logic of capitalist relations. In an interview, a co-op worker lamented: “We took it over. We were so excited. We made our wages equal. We instituted democracy. We had a workers’ council. We made our decisions democratically. And after a period of time, all the old crap came back. All the old alienation came back, and now it just feels the way it used to feel.”

State-sponsored cooperatives operating under the constraints of capitalism also face fundamental contradictions. ‘Socialism in the 21st century’ in Venezuela saw the Hugo Chavez government encourage the setting up of 280,000 cooperatives and ‘mixed enterprises’ from 2002 to 2008.

Such measures, along with a limited redistribution of oil wealth, improved the lives of many of the poorest people. But the decisive sectors of the capitalist economy remained untouched and capitalist relations inevitably dominated the economy. Bribery and corruption were rife in many state and municipal bodies, and many of them registered as co-ops to take advantage of government subsidies.

Co-ops may be formally cooperatively and democratically run, but seeking to succeed on the capitalist market means that they are governed by the logic of competition.

‘A Manifesto for union co-ops’, launched in 2020 by Union-Coops UK, calls for “a fully unionised, worker co-operative, owned and controlled by those who own and work in it”. The union co-op model, developed in the United States in recent years, is an attempt to link co-ops to the wider workers’ movement. It also indicates recognition of the need for organised labour in co-ops, where class tensions find expression.

These are laudable aims. But the analysis made over 150 years ago by Marx remains valid: “The experience of the period from 1848 to 1864 has proved beyond doubt that, however excellent in principle and however useful in practice, cooperative labour, if kept within the narrow circle of the casual efforts of private workmen, will never be able to arrest the growth in geometrical progression of monopoly, to free the masses, nor even to perceptibly lighten the burden of their miseries… To save the industrious masses, cooperative labour ought to be developed to national dimensions, and, consequently, to be fostered by national means… To conquer political power has, therefore, become the great duty of the working classes.” (Marx, 1864 Inaugural Address to the Working Men’s International Association).

The socialist reorganisation of society, on a national and international level, including the nationalisation of the commanding heights of the modern economy under democratic workers’ control and management, is the starting point for the realisation of the development of society towards the ‘classless, communist’ dream of the early cooperative pioneers.

Niall Mulholland (writing in a personal capacity) is chair-elect of a housing cooperative in East London (UK) and an elected executive member of the London Federation of Housing Cooperatives