With the rising tide of pay strikes and ballots, there is much talk of a ‘summer and autumn of discontent’, with comparisons to the 1978-79 so-called ‘winter of discontent’ being drawn in Britain.

Due to the Tory media’s vitriolic attacks on the strikers at the time, and repeated ever since, the winter of discontent is mainly remembered by many as the ‘dirty jobs strike’, with images of rubbish in the streets and the dead going unburied.

But in reality, it was a four-month period of a series of local and national strikes by mostly low-paid workers, many of them women, for pay rises to catch up with inflation, against a Labour government’s pay restraint policy. It involved 4.6 million people in strike action. It included a one-day strike by 1.5 million council manual workers and NHS ancillary staff, which was the biggest strike day since the 1926 General Strike.

Are we heading for something similar today?

There are certainly many similarities with the situation in 1978. The end of the post-war economic boom was marked by a quadrupling of oil prices following war in the Middle East, resulting in very high inflation, peaking at 27% in Britain in 1975. Today we have the highest inflation rate for 40 years.

While it was a Labour government from 1974-79, like the Tory government today, it was very weak. Its small parliamentary majority gained in two elections in 1974 was eroded by by-election losses which eventually left Prime Minister James Callaghan dependent on Liberal Party, Scottish Nationalist and even Ulster Unionist votes, before finally losing a parliamentary vote of confidence in March 1979.

Labour had been pushed into office by the power of working-class people in trade unions, that had brought down the previous Tory government of Ted Heath. He had tried to face down strikes with a snap “who runs the country?” general election in February 1974. He lost.

Labour’s chancellor Denis Healey promised to “squeeze the rich until the pips squeak”. But workers’ hopes in a Labour government were quickly disappointed. Rather than implement socialist policies when met with economic difficulties, in September 1976 Healey ran to the International Monetary Fund for a loan to support the currency, in exchange for which he agreed big cuts in public spending and wage restraint to curb inflation. Instead of standing up to big business, the Labour government did their bidding.

Inflation

Like today, wage rises were falsely blamed for inflation or causing a wage-price spiral. Like the Tory governments of the last 12 years, the Labour government imposed wage restraint. Initially this was with the voluntary agreement of the union leaders in the Trades Union Congress (TUC). This was called the ‘social contract’. In exchange for the trade unions restraining pay demands, i.e. accepting real terms pay cuts, the Labour government promised to maintain public spending. They quickly reneged on this. But the union leaders, including the ‘left’ ones, fearing another Tory government, still held their members back.

So with a few exceptions, most notably the ten-week firefighters’ strike in 1977, which the TUC did not support, the Labour government was able to hold wage rises down for three years to the well-below inflation limits they set, without provoking much industrial action. But like today, successive real-term pay cuts meant that workers’ anger eventually exploded in a wave of strikes.

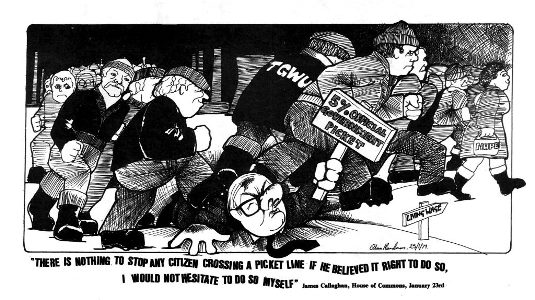

With inflation still at 10% in 1978, Callaghan imposed a 5% pay limit. At last, feeling pressure from below, this was without TUC agreement – although only on the General Council chair’s casting vote.

Pay cuts rejected

It was Ford motor car workers in the private sector who were the first to break through. Rejecting the company’s initial 5% offer, 57,000 Ford workers struck in September for two months, rejecting several ‘final offers’ before settling for a 17% pay rise.

It’s been the RMT rail union (followed by Aslef and TSSA) in the privatised railways and the Communication Workers Union in privatised BT and Royal Mail who have been leading the way today. Ballots of public sector workers are being prepared in local government, universities, teachers, civil servants and most likely NHS workers and firefighters.

The Ford workers’ victory broke the floodgates in the same way the recent RMT strikes have transformed the mood and confidence of workers. Bakery workers struck for six weeks in November and December 1978, then road haulage lorry drivers, organised in the TGWU transport union, now part of Unite, struck through January 1979, eventually winning a 20% rise.

On 22 January, the four public sector and health unions called a one-day strike for a £60 minimum wage for a 35-hour week. One and a half million workers struck that day, predominantly low-paid, council manual workers and NHS ancillary staff. 100,000 marched in London.

This led to ongoing local and national strikes by refuse collectors, gravediggers, ambulance drivers and hospital workers, and later civil servants gaining pay rises of between 9% to 14%. With the Labour government hanging by a thread in parliament, the trade union leaders were desperate to end the strikes and agreed a ‘concordat’ with the government in mid-February, ending the strike wave.

The winter of discontent had an element of being a rolling general strike, which could be repeated today as unions name different days and lengths of strike action. That’s why the National Shop Stewards Network (NSSN) has called for a lobby of September’s TUC Congress to demand coordinated strike action.

The TUC has called a lobby of parliament on Wednesday 19 October. The Socialist Party calls for this to be turned into a massive demonstration, bringing together private and public sector workers in a show of workers’ power, which would raise the confidence and consciousness of the organised working class and beyond.

Trade union strength

However, there are differences with the situation today compared with 1978-79. Then, over 13 million workers were trade union members, twice the figure now. Over 50% of all employed workers were in a trade union and 75%-80% of employees were covered by trade union collective agreements. Workers had not recently suffered any major national defeats; in fact quite the opposite. Trade union power supported by working-class votes had effectively brought down the Tory government only four years earlier. Whereas most workers today can’t even remember the last time our side won in a major national dispute. In 2019, only 290,000 working days were lost through strikes, 1% of the 29 million lost in 1979.

The strength of the trade union movement, built up during the post-war economic boom, was also represented in the 1970s by the 350,000 shop stewards and workplace reps elected in industry and the public sector, who exercised pressure on the trade union leaders and often acted independently.

The Heath government had introduced anti-trade union laws, but these were defeated by several major strikes in 1972, especially the semi-spontaneous general strike that developed from below to release the ‘Pentonville Five’ dock shop stewards who’d been jailed. This meant that in the late 70s there weren’t any effective trade union laws in place. So, unlike today, workers could ‘down tools’ and walk out on strike without a ballot, and could picket other workplaces to ask for solidarity action, so-called secondary picketing, all of which is illegal now – and the Tories plan measures to clamp down further.

Many of the 78-79 strikes started unofficially, such as at Fords and the lorry drivers. Or they continued unofficially in the case of sections of council and NHS workers, usually made official later by reluctant trade union leaders. Secondary picketing and solidarity action was a big feature as well: the lorry drivers picketed ports, refineries and ‘scab’ haulage firms.

Workers’ control

Shop stewards committees and strike committees often played the leading role at a local level. ‘Dispensation committees’ were established in some cities, notably Hull, by striking lorry drivers, which decided on emergency supplies. This occurred in the NHS ancillary strikes as well, with shop stewards deciding on emergency cover levels. This showed a high level of workers’ control which scared the bosses, the government, and the trade union leaders. Thatcher, then the opposition Tory leader, screeched in parliament: “Now we find that the place is practically being run by strikers’ committees… They are ‘allowing’ access to food. They are ‘allowing’ certain lorries to go through…”

Trade unions are not at that level today. But the forthcoming strike wave will afford the opportunity for workers, especially the new generation of young workers, to rebuild and re-energise the movement through collective and coordinated strikes, demonstrating the real power of the organised working class.

This cost-of-living crisis is severe. The draconian anti-trade union laws cannot be allowed to stand in the way of effective action, especially if that poses the real possibility of bringing down a weak and divided Tory government, as in 1974. As Unite general secretary Sharon Graham has said, “If you force our legitimate activities outside of the law, then don’t expect us to play by the rules.”

The beginning of a resurgence in trade union action has, given the anti-union and pro-business positions of Starmer’s Labour, understandably led to some left trade union leaders and many of the best activists thinking that trade union power alone is enough to fight the bosses, the Tories, and the capitalist system.

However, a big lesson from the winter of discontent is that workers do need political representation. Despite demonstrating trade union power and winning some big wage rises, disillusionment with the pro-capitalist policies of the Labour government led many workers to stay at home in the May 1979 general election. Margaret Thatcher won, ushering in 13 years of Tory and anti-union rule.

In the early 1980s, the democratic structures and participation of working-class people meant that a major battle was possible in the Labour Party to fight to change it. The left in the party, including supporters of Militant (forerunner of the Socialist Party), and those around Tony Benn, won support among the members for democratic changes and more socialist policies.

That is impossible now in Starmer’s Blairised Labour Party, with democracy and the trade union voice shut down, and Corbyn’s pro-worker policies driven out. It makes it essential that trade unions stop funding an anti-union party and begin the process of building a new, trade union-based, working class and socialist party.